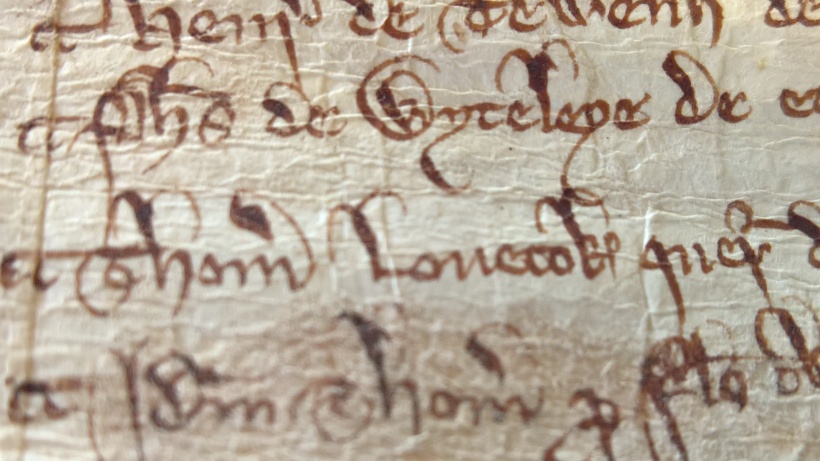

(Image from Halesowen Manor Court Rolls, Wolfson Centre Archive, Birmingham, MS 346261)

The people appearing in medieval manorial records are identified by first name, surname and various relationships as well as offices. Nicknames as identifiers were still very common throughout the 14th and into the early modern period, but historians have quite rightly identified a development whereby surnames tend to become more fixed in the course of teh 14th century. To confuse matters individuals might be referred to by various names in manorial documents. Let us take a fictitious Richard Gruggan, for example. He might be identified as Richard the Hayward ( as he was the manor’s acting hayward) in one court roll, or Richard Gruggan in the next roll. Richard is also the son of Adam Gruggan, so he might be referred to as Richard the son of Adam, or Richard Adamson. Let’s say Richard had red hair, which, his neighbours felt was a sufficiently notable feature to make him stand out from the crowd, so some days Richard the Redhead makes an appearance. Such issues cause potential methodological mayhem for people like myself, who spend a lot of time analysing networks and reconstructing familial relationships.

However, such methodological headaches is not what concerns me primarily today. I find the nicknames people gave to each other fascinating and compelling, and in truth little work has been done to analyse these. Nicknames were very descriptive, although it is not always clear to what extend they were ironic. John the Monk, for example might make us smile, but was he nicknamed ‘Monk’ because he was very pious or because he was the opposite? Richard the Pope might also fall into this category. A poor cottager referred to as ‘the king’ certainly has a ring of sarcasm to it. Other nicknames are focused on character or appearance. ‘The Redhead’ or ‘the Red’ is far from uncommon, nor is ‘the skinny’, while ‘the cripple’ is rarer. In particular nicknames have, in my view, a clear gendered dimension.

Interestingly, and I have to stress that I have not yet conducted any in- depth empirical research into this issue, so my points here are based on impressions, women have fewer nicknames than men. Women are much more often identified through their occupations, like Heacham’s Agnes the Fisherwoman, regular surnames or marital relationships than their habits, characters or looks. Still some women are identified by nicknames, and sometimes women’s nicknames are rather touching, and somehow feel more emotive than the nicknames of men. Matilda ‘the Blossom’ falls into that category for example, or Agnes ‘the Sweet’. One set of nicknames appears to have been entirely absent in reference to women, and these are sexual in nature. Across several manors I have come across many men who were frequently referred to as ‘loverboy’ or more rarely but also more explicitly ‘lovecock’ or ‘lover’ but never a women. The reasons must be obvious. Women and men were very concerned to maintain their reputations, manorial courts regularly feature both men and women suing their neighbours for calling them potentially defamatory names. There was nothing worse than calling a merchant a thief, or indeed a woman a whore. So here is a clear gendered dichotomy. Men were perfectly able to go around calling themselves or each other ‘loverboy’ while women could not. The acceptability of the use of sexualised nicknames for men thus represented a mechanism for social control within medieval communities re-enforcing the idea that sex for men – even perhaps outside marriage – was acceptable – and perhaps something even to be proudly legitimised- as it was entered into court records, while for women this was – at least officially taboo. Maybe one day I will write an article on this, as it strikes me as rather interesting.